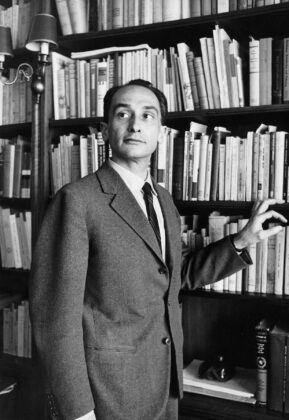

The life of

Giovanni Sartori

A man “larger than life”

1924

I was born in Florence in 1924. I thus have vivid memories of Fascism, of the war with Abyssinia, of the Spanish Civil War (in which Franco was assisted by Italian soldiers), and, of course, of World War II. It goes without saying that my lifelong concern about democracy – solid rather than advanced democracy – arises out of these “dark” memories of Fascism and Nazism.

1925-1945

The war years

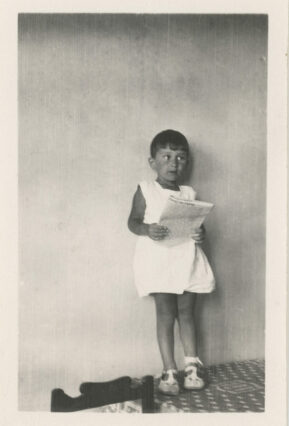

Italy’s war in alliance with Hitler ended in surrender on September 8, 1943. In that year, I had expected to be and dreaded being drafted (I was nineteen) and sent to war. But the Italian military machine was, after all, Italian and thus behind schedule. My call to arms came up only in October 1943, and came from the newly installed Fascist puppet regime known as the Republic of Salò. Like most of my peers, I sought escape in hiding. The penalty for deserters was, however, to be shot on the spot, and whoever hid a deserter equally risked his or her life. I thus spent some ten months “buried” (for I was not allowed even to be seen within the house-hold) in a somewhat hidden room until Florence was liberated from German occupation in August 1944.

1925-1945

The war years

Italy’s war in alliance with Hitler ended in surrender on September 8, 1943. In that year, I had expected to be and dreaded being drafted (I was nineteen) and sent to war. But the Italian military machine was, after all, Italian and thus behind schedule. My call to arms came up only in October 1943, and came from the newly installed Fascist puppet regime known as the Republic of Salò. Like most of my peers, I sought escape in hiding. The penalty for deserters was, however, to be shot on the spot, and whoever hid a deserter equally risked his or her life. I thus spent some ten months “buried” (for I was not allowed even to be seen within the house-hold) in a somewhat hidden room until Florence was liberated from German occupation in August 1944.

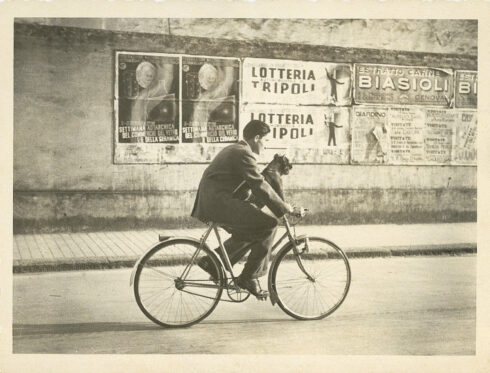

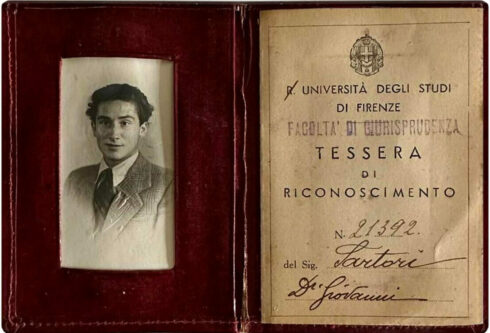

1946-1949

The years at the University of Florence’s “Facoltà Cesare Alfieri”

I earned my doctorate in social and political sciences at the University of Florence in November 1946, and for the next four years I had nothing better to do than to linger on. The country was largely in a shambles and the university had many of its “barons” (i.e., tenured professors) under purge, suspended, or indicted for having been Fascists. Since I was considered an enfant prodige (remember, I was supposedly able to understand Hegel), I immediately was appointed assistant to the chair of General Theory of the State – the equivalent of the German Staatslehre – and in fact my assistance went as far as to do almost all the teaching in lieu of my frequently absent professor. His name was Pompeo Biondi.

1949-1950

After the early grant that brought me to New York in 1949-50 (shopping between Columbia and the New School for Social Research to the U). While as a politologo I was largely self-taught (I had no teachers). In learning by myself, I could and did rely on the international context (the IPSA context), on my entering the path-breaking IPSA Committee of Political Sociology (where I made lifelong outstanding friends: Marty Lipset, Juan Linz, Stein Rokkan, Matte Dogan, Hans Daalder, S.N.Eisenstadt),.It is quite evident that had I not been exposed to the science of politics that blossomed after World War II in the United States, I would have been an entirely different scholar.” I returned many times United States in the 1960s, first as a Visiting Professor of Government at Harvard (1964-65), and subsequently as a recurrent Visiting Professor of Political Science at Yale between 1966 and 1969.

1949-1950

After the early grant that brought me to New York in 1949-50 (shopping between Columbia and the New School for Social Research to the U). While as a politologo I was largely self-taught (I had no teachers). In learning by myself, I could and did rely on the international context (the IPSA context), on my entering the path-breaking IPSA Committee of Political Sociology (where I made lifelong outstanding friends: Marty Lipset, Juan Linz, Stein Rokkan, Matte Dogan, Hans Daalder, S.N.Eisenstadt),.It is quite evident that had I not been exposed to the science of politics that blossomed after World War II in the United States, I would have been an entirely different scholar.” I returned many times United States in the 1960s, first as a Visiting Professor of Government at Harvard (1964-65), and subsequently as a recurrent Visiting Professor of Political Science at Yale between 1966 and 1969.

1951-1956

Now the story of how it happened that I found – or authoritatively was given – my vocation, my Beruf. The year was 1950. At a faculty meeting, the Dean, Maranini, told his unsuspecting colleagues that he had a promising young marvel to propose:

Giovanni Spadolini, who was then 25 years old (one year younger than I was), and later became managing editor of the Corriere della Sera (the major Italian daily paper), minister, prime minister, and president of the Senate, and just missed by a hair’s breadth the presidency of the Republic. As this record shows, Maranini had indeed picked a winner. But Pompeo, my boss, could not accept the loss of face of not having a candidate of his own. On the spur of the moment, he proposed me (as his counter-genius), and the first vacant teaching post that flashed across his mind was History of Modern Philosophy. The deal was struck – both Spadolini and Sartori – and I was appointed on the spot “professore incaricato” (assistant and/or associate professor: there was no difference at that time). I was unsuspecting and was just informed the next day that I had to teach history of philosophy (as I did for six years, 1950-56).

1957-1963

Pioneer of political science in Italy

Remember that philosophy was, for me, a war “accident.” I was mainly interested in logic, not in philosophers. But logic was not taught in Italian universities and was, indeed, anathema for both idealistic philosophy and Marxist dialectics (the dominant schools). I had to work my way out. It would take too long to rehearse how a combination of stubbornness but also, again, of fortunate coincidences allowed me to move to political science. Skipping all the many amusing anecdotes, by 1956 I had managed to have political science entered in the statute (the list of recognized and permitted teachings) of the Florence Faculty of Political Sciences, which had previously encompassed teaching on law, history, economics, statistics, geography, philosophy. I was able to switch (always as a professore incaricato) to this entirely novel and, for many, suspect academic discipline.

1957-1963

Pioneer of political science in Italy

Remember that philosophy was, for me, a war “accident.” I was mainly interested in logic, not in philosophers. But logic was not taught in Italian universities and was, indeed, anathema for both idealistic philosophy and Marxist dialectics (the dominant schools). I had to work my way out. It would take too long to rehearse how a combination of stubbornness but also, again, of fortunate coincidences allowed me to move to political science. Skipping all the many amusing anecdotes, by 1956 I had managed to have political science entered in the statute (the list of recognized and permitted teachings) of the Florence Faculty of Political Sciences, which had previously encompassed teaching on law, history, economics, statistics, geography, philosophy. I was able to switch (always as a professore incaricato) to this entirely novel and, for many, suspect academic discipline.

1964-1972

My idea of political science

By 1963 (it took me seven years of waiting, but still much less than my statistics predicted), I was the first and only tenured professor of political science in Italy. To be sure, I had to use a back door: I won a chair in sociology. But once “chaired,” it was easy for me to return to political science. Against all odds, I had made it. The next and immediate task was to promote and establish the discipline.

I must now take a step back. Why political science? And, further, how did I conceive the discipline and land in comparative politics? In truth, I am only a part-time comparativist. My work can be divided in three slices: (1) straightforward political theory; (2) methodological writings where methodology is understood as the method of logos, of thinking, not as a misnomer for research techniques; and (3) comparative politics proper.

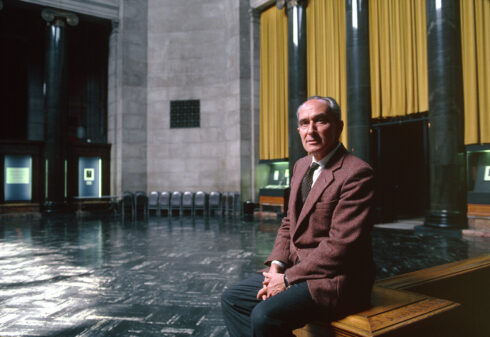

1973-1979

Away from Italy, between Stanford and the Columbia University

In 1971-72, pretty much worn out by some three years of battles (it was quite rough in Italy), I went to Stanford, where I spent a delightful and fruitful year “on the hill” as a fellow of the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. Thereafter, in 1976, I somewhat suddenly decided to leave Italy time. Stanford offered me the position that Gabriel Almond was leaving. Stanford put all the distance from Italy that I needed. But then, out of the blue, I received an offer from New York that could not be refused. After three years, in 1979, I left Stanford and became Albert Schweitzer Professor in the Humanities at Columbia University, where (since 1994) I am Professor Emeritus.

1973-1979

Away from Italy, between Stanford and the Columbia University

In 1971-72, pretty much worn out by some three years of battles (it was quite rough in Italy), I went to Stanford, where I spent a delightful and fruitful year “on the hill” as a fellow of the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. Thereafter, in 1976, I somewhat suddenly decided to leave Italy time. Stanford offered me the position that Gabriel Almond was leaving. Stanford put all the distance from Italy that I needed. But then, out of the blue, I received an offer from New York that could not be refused. After three years, in 1979, I left Stanford and became Albert Schweitzer Professor in the Humanities at Columbia University, where (since 1994) I am Professor Emeritus.

1980-1994

The influence of US political science

This quick account suffices to indicate the extent of my exposure to American political science. At Harvard I met, or got to know better, Carl Friedrich, Talcott Parsons, Sam Beer, Sam Huntington, Henry Kissinger; at Yale, Robert Dahl, Harold Lasswell, Karl Deutsch, Charles Lindblom, David Apter, Joe LaPalombara; at Stanford, Gabriel Almond, Marty Lipset, Robert Ward; at Columbia, Robert Merton (I had attended his class in 1950), Zbigniew Brzezinski, Severyn Bialer, and others. One always benefits from the company of good, indeed very good, minds. But reading is, as a rule, more important. The work that perhaps influenced me more than any other was Dahl’s A Preface to Democratic Theory (1956). When I read it, I was thunderstruck by Dahl’s method, by his systematic analysis of “conditions” (an exercise that Dahl repeated in the early 1960s, under my ever-admiring eyes, at the Bellagio Rockefeller Center for the volume Political Oppositions in Western Democracies, 1966).

1995-2017

The public intellectual

As of 1994, I lived mainly between New York and Rome. When my academic activities came to an end, I devoted myself mainly to my role as a public intellectual, making publicly available my knowledge and skills. In fact, it was during this period that I intensified my activity as a columnist for the most important Italian newspaper “Corriere della Sera”, dealing with both “old issues” (such as the institutional reforms in Italy) and new pressing concerns (starting with climate change). It was also the period of international prizes and awards for me, receiving several Honorary Degrees and being awarded, in 2005, the prestigious “Principe de Asturias” prize. In the meantime, I kept writing essays, focusing on some of the most pressing issues of our time – the impact of new media on public opinion (Homo videns), the consequences of migration on contemporary society (Pluralism, multiculturalism and strangers), the effects of climate change and overpopulation (The Earth Explodes), and finally the risks to the future of democracy (The Race to Nowhere).

Giovanni Sartori died in Rome on April 3, 2017, and his ashes rest in the family chapel at the San Miniato Cemetery in Florence.

1995-2017

The public intellectual

As of 1994, I lived mainly between New York and Rome. When my academic activities came to an end, I devoted myself mainly to my role as a public intellectual, making publicly available my knowledge and skills. In fact, it was during this period that I intensified my activity as a columnist for the most important Italian newspaper “Corriere della Sera”, dealing with both “old issues” (such as the institutional reforms in Italy) and new pressing concerns (starting with climate change). It was also the period of international prizes and awards for me, receiving several Honorary Degrees and being awarded, in 2005, the prestigious “Principe de Asturias” prize. In the meantime, I kept writing essays, focusing on some of the most pressing issues of our time – the impact of new media on public opinion (Homo videns), the consequences of migration on contemporary society (Pluralism, multiculturalism and strangers), the effects of climate change and overpopulation (The Earth Explodes), and finally the risks to the future of democracy (The Race to Nowhere).

Giovanni Sartori died in Rome on April 3, 2017, and his ashes rest in the family chapel at the San Miniato Cemetery in Florence.